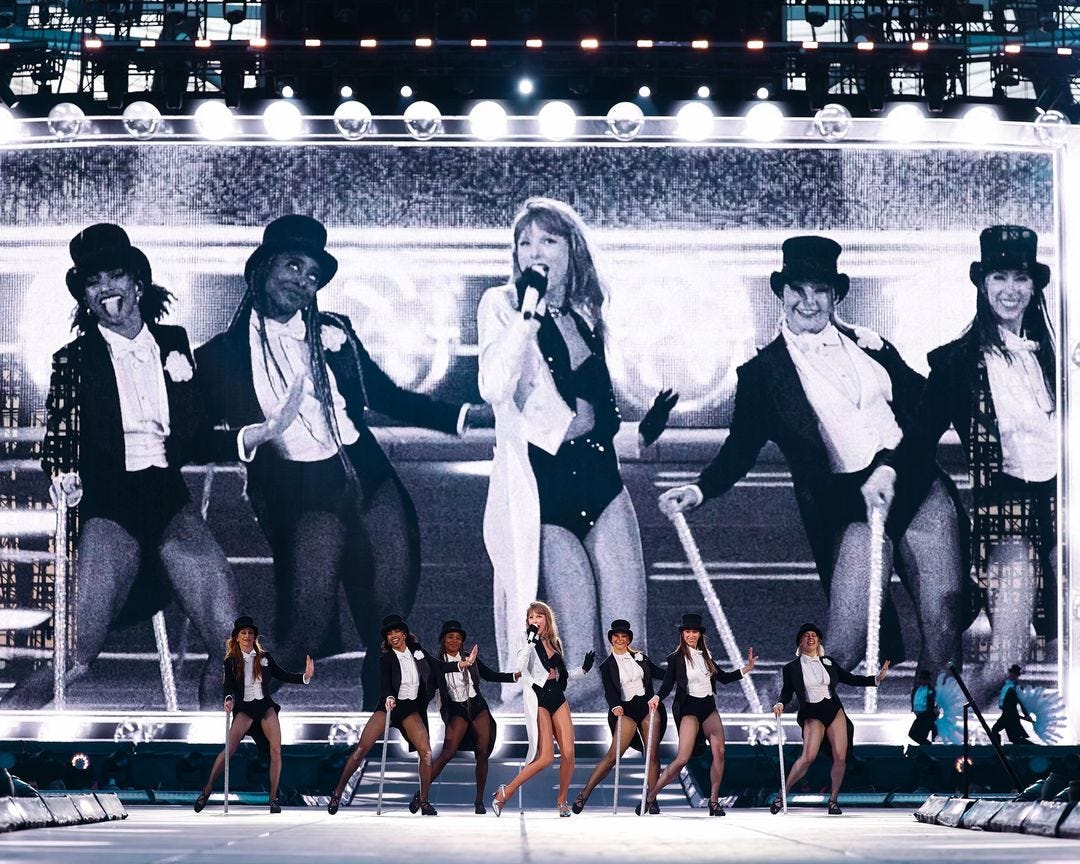

Taylor Swift’s sparkly ballad “I Can Do It With a Broken Heart” highlights a harsh reality for many individuals struggling with their mental health: the need to hide their pain behind a mask of resilience. As a clinical psychologist, I see this behavior often—individuals who, due to societal expectations or internalized shame, feel compelled to conceal their emotional distress. This is commonly referred to as “masking.”

Lights, camera, bitch, smile, even when you wanna die

Masking refers to the conscious or unconscious camouflaging of one’s true emotions or mental state in order to fit in, appear “normal,” or meet societal expectations. People who mask often present a facade of well-being or competence while struggling internally with trauma, depression, anxiety, or other forms of mental distress. The phrase “Lights, camera, bitch, smile, even when you wanna die” from Swift’s song concisely reflects this performative pressure: smiling through overwhelming emotional pain.

For trauma survivors, masking can operate as a coping mechanism that ensures survival in environments that are not conducive to vulnerability. Furthermore, unresolved trauma can hijack the nervous system in a way that makes individuals feel perpetually unsafe, even in neutral or safe situations. As a result, masking for the trauma survivor becomes a reflexive protective mechanism against anticipated harm.

If we were to unpack the psychological factors that drive the need to mask emotions, we’d find three central determinants: survival, social pressure, and fear of rejection. Related to survival, it is commonly accepted that trauma activates the brain’s survival system. As a result, when a person feels threatened, they may hide their distress to avoid further emotional or physical harm. Research has shown that childhood trauma, in particular, is associated with chronic hypervigilance, where individuals are constantly on alert for danger (van der Kolk, 2015).

Concerning social pressure, we live in a society where there is extraordinary pressure to conform to social norms and expectations. Swift’s lyrics, “I’m a real tough kid, I can handle my shit,”underscore the societal demand to appear “tough” and in control, even when it feels impossible. For many, masking becomes a way to meet social expectations that value stoicism and independence, even when their internal reality is one of excruciating struggle.

Finally, a driving force behind masking is fear of rejection. Recent studies on social stigma and mental health reveal that people often hide emotional distress out of fear of being judged or ostracized (Jones & Grubbs, 2020). Many trauma survivors have a deep-seated fear of abandonment stemming from past relational experiences. Consequently, they may cloak their emotions to prevent others from seeing them as “weak” or “broken.”

All the pieces of me shattered as the crowd was chanting, “More”

While masking may offer short-term protection from emotional pain, it can have serious long-term effects on mental health. Chronic masking can lead to emotional burnout, isolation, and delayed healing. The constant effort of pretending to be okay is mentally and physically draining. Swift’s lyric, “All the pieces of me shattered as the crowd was chanting, ‘More’” refers to the exhaustion of maintaining a facade when you feel like you’ve crumbled inside. Over time, this leads to burnout and emotional fatigue, making it even harder to engage in daily life or form authentic connections. Masking often creates an incongruence between a person’s true self and the image they project to the world. This discordance can create feelings of isolation, as it becomes harder for others to truly understand or support the person behind the mask.

I’m so depressed, I act like it’s my birthday everyday

One of the most tragic consequences of masking to me as a therapist is that it can prevent people from accessing the support they need. When trauma survivors mask their pain, they are less likely to seek help from therapists, friends, or family members. This prolongs their suffering and can worsen symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. A 2019 study on emotional suppression in trauma survivors found that individuals who chronically suppressed their emotions were more likely to develop long-term mental health issues, including PTSD (Cloitre et al., 2019).

Swift’s “I Can Do It With a Broken Heart” opens up an important dialogue about mental health that can help break down the barriers that force people to mask their pain. As a society, we need to challenge the “fake it till you make it” mentality and embrace vulnerability as a form of strength, not weakness.

References:

- Cloitre, M., Khan, C., Mackintosh, M. A., & Garvert, D. W. (2019). Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between trauma exposure and social functioning in adults with and without childhood trauma exposure. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(6), 933-944.

- Jones, A. J., & Grubbs, J. B. (2020). Understanding the role of stigma in predicting mental health treatment outcomes among trauma survivors. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(4), 743-758.

- van der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books.